I know that I mentioned in another post that it’s Buffy’s fault that I’m gay. But I’m gay enough for the causes to be diffuse and plentiful. So, here’s another round of trying to explain the unexplainable.

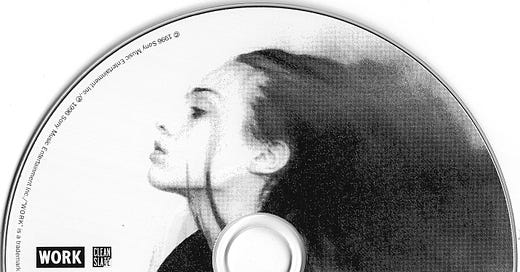

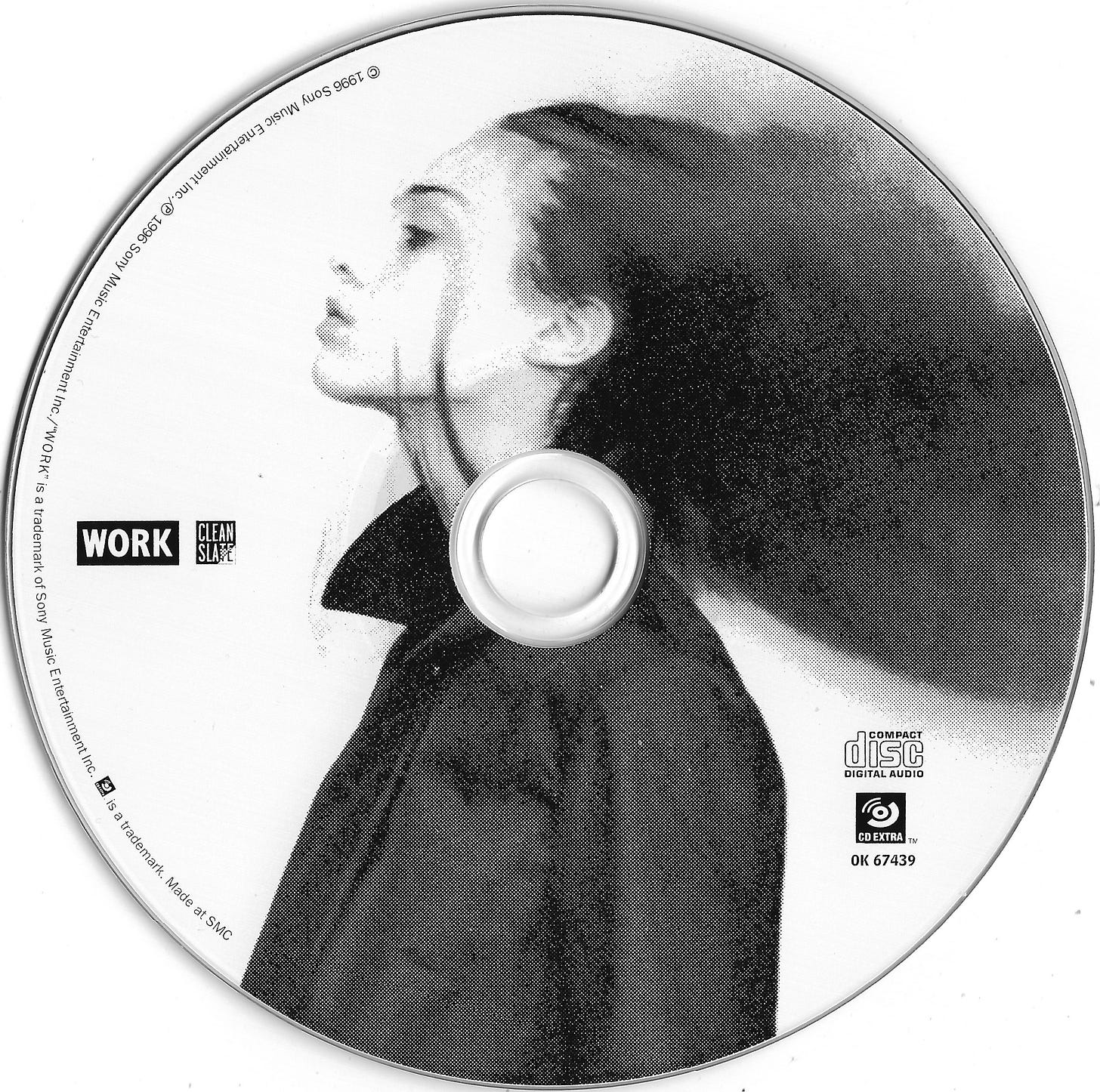

I snuck into my older sister’s room first thing in the morning. My toes sunk into her plush aquamarine carpet that I coveted so fiercely. She had slept over a friend’s house the previous night. Her window faced the front of the house. A furtive glance outside confirmed my suspicion and hope that my dad had left for work. I raided her CD binder, selecting the prettiest disks I could find — arcane markings on some; others bright pink; some simply shiny metallic with a band’s name in sharpie. This routine used to involve stealing her dolls when I was a little kid; lately, it had graduated to music. This time, I chose the black and white CD with a girl standing in profile, hair flying back behind her head. As I watched through the transparent blue cover of my beloved CD Walkman, the disk created the illusion of her doing somersaults in time with her music. Fiona Apple’s Tidal.

On the hardwood floor of my room, I made my Star Wars action figures dance to “Criminal” and “Shadowboxer.” I recognized Apple’s music from the previous weekend when I’d peeked into a sleepover my sister was having in the basement. Illicitly, they were watching VH1. Peering around the corner, I’d watched the TV over my sister and her friends’ shoulders. Childlike, Apple seemed stuck in bedrooms, crawling around on beds, ruminating on her immobility. She seemed remarkably incapable of even sitting upright in a chair. I related now, sprawled on the floor alone.

I imagined my plastic figures were in a cantina on Tatooine and that she was there, serenading an audience of aliens. I knew the premise of Star Wars, but I didn’t care much about the specifics of the plot. I had accumulated the action figures at some point as a default boy version of the Barbies I wished my parents would’ve bought me. Still, I enjoyed them as much as I could. The light sabers became dance accessories; the Jedi cloak a flowing dress. I decked out my favorite — Princess Leia. Cruelly, her hair wasn’t manipulable. It was hard plastic, buns locked to the side of her head. Boys’ toys’ inflexibility was hostile architecture, guaranteeing that I couldn’t “misuse” them. Virtually no time could be spent on styling Leia. I once made and abandoned a plan to hot glue brown thread over her hard plastic hair so that I could see her with her hair down. I could shake her; the hair would flow. But I was worried that it would ruin the toy; worse, Brad, my best friend, would ask me what happened to her. What would I say? That I wanted to practice my braiding skills? In lieu of hair styling, inventing dance moves for her would have to suffice. I made Leia swing around, like a shadowboxer.

Eight years later, I was sixteen and it was Christmas Eve. I’d just told my middle-school girlfriend via AOL instant messenger that I was gay. The first person I’d ever told. I typed and hit send quickly, before I could take it back. Something about the whole process pissed me off. Suddenly my secret became hers—she who I hadn’t talked to in three years. What the hell did I get out of this? Coming out, I learned, was a bit like toothpaste; once the truth is out, it’s out. And I couldn’t use it anymore; it was just a mess.

Later that week, I was Christmas shopping at a record store in the South Side neighborhood of Pittsburgh when I saw this poster stapled to the ceiling of Fiona Apple licking a lit match—staples puncturing the poster and dotting her hairline. I hadn’t listened to her in years. She seemed to be pissed about it: “hey remember me? Since you last saw me, I’ve become impervious to fire.”

I wanted that, too.

My passion for her was reignited: what would she sound like to me now? To a me who isn’t worried that I’d get caught listening to her? To a me who’s out, disoriented, and a little pissed off?

I picked up a copy of her first album, Tidal, and fell for her harder than I ever let myself as a kid. As a bonus, she happened to be having a resurgence in that same moment: her album, Extraordinary Machine, had just come out. A budding fanboy, I obsessively sketched out a map of the three albums she’d released, noting differences and evolutions. Each new album she’s released since that moment of reignition has realigned my world, shattering and reconstituting the arc of her canon and, by extension, my understanding of myself.

Perhaps one reason I needed Fiona Apple so acutely when I came out was because she’s a master of navigating the vertigo that comes with sudden and disorienting visibility.

Fiona Apple is famous as hell. She has an enduring presence. And yet she’s almost invisible. Stories proliferate about how she haunts popular music and culture. I can listen all day to stories about Jennifer Lopez begging for the rights to Criminal for the movie Hustlers. In a rare move (she almost never allows her music to be used for movies), she enthusiastically gave Lopez the rights. I like to think of the two of them honoring some kind of 90s female pop star trauma bond.

It’s amazing how much she permeates culture even without being visible in it. What I respect so much about her invisibility is how, when she becomes visible, she does it with brave intention. Perhaps the injustice of this forced invisibility was what inspired her once-infamous, now legendary, VMAs speech where she excoriates the music industry for turning people against each other and themselves. She encourages people to trust their own instincts; not to be drawn in by fame.

Since Trump won his second term and threatened increased deportations, I’ve seen a now-classic video circulating on social media. In it, Apple narrates an animated film about how to safely and effectively document ICE arrests. She originally taped it at the end of Trump’s previous term; now, it’s needed more than ever. During times of emotional and political uncertainty (such as the collapse of our democracy) I often turn to Apple’s music, so it’s no surprise that she’s appearing in other peoples’ feeds as well.

Apple really only emerges every five to ten years with a new album, but her appearances in between offer inflections of pure moral clarity: for example, her 2016 performance at the "We Rock With Standing Rock" benefit concert for the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe’s water protectors, or her 2017 anti-Trump protest chant: “We don’t want your tiny hands anywhere near our underpants.” She lays low until you finally find her; and when you do, she appears to have already been, for a long while, elbow-deep in society’s bullshit, like Laura Dern in Jurassic Park.

“This world is bullshit,” said Apple, first at the 1997 VMAs, and subtly, implicitly, constantly, ever since. She wasn’t interested in ever going along with things; she always wanted to face the world with the mess it’s made. She doesn’t seem exhausted, but rather focused; perhaps because she’s so comfortable in the role of the hermit most of the time. It feels like she’s been saving up her batteries for moments of actual impact.

She’d been shuffling through the muck for a while in order to come up with the brilliance of her latest album, Fetch the Bolt Cutters. In Fiona Apple’s first album, she swum through deep interior landscapes. As a young kid, I couldn’t always relate to the specifics of those landscapes, but I could relate to the feelings of isolation that she articulated so beautifully. In “Sullen Girl,” she frames the isolation as a problematic solution:

“And there’s too much going on; but it’s calm under the waves in the blue of my oblivion.”

Then, she began to come out of her shell. Almost ten years later, in “Parting Gift” (Extraordinary Machine, 2005), she laments how invisible she’s made herself:

“I took off my glasses while you were yelling at me once, more than once, so as not to see you see me react. Should've put 'em on again so I could see you see me sincerely yelling back.”

She’s reacting to isolation from others by further isolating herself. She can only survive by making herself less visible.

With Fetch the Bolt Cutters (2020), Apple shows other pathways to survival by doing the a kind of feminist work that she’d never explored before. If it were possible to somehow ignore gender in her earlier albums, it becomes jarringly unavoidable in this one. “Ladies” offers a bold attempt to make a long-overdue amends with other women by literally, repeatedly addressing them. The address, a simple, playful repetition—“Ladies, ladies, ladies, ladies”—clashes against the comically convoluted repeated verse:

“Ruminations on the looming effect and the parallax view, and the figure and the form, and the revolving door that keeps turning out more and more good women like you.”

It would seem, with the durability and power of heteropatriarchal structures keeping women apart, that it would take a rocket scientist to solve it. But, Apple, suggests, what if we met that complexity by simply reaching out to one another? Of course, it’s not always that simple. In “Newspaper,” Apple argues that one characteristic of abuse is its isolation of women from hearing one another: “It’s a shame because you and I didn’t get a witness. We’re the only ones who know. We were cursed the moment that he kissed us.” It is nearly impossible to break out of a sexist paradigm—at least, when women are being watched. Which may help to explain Apple’s voluntary isolationism.

In her brilliant article, “Fiona Apple’s Art of Radical Sensitivity,” Emily Nussbaum describes Apple currently living in a “Boston marriage”—a deep, platonic intimacy—with another woman. In the classic queer and feminist essay, “Compulsory Sexuality and Lesbian Existence,” Adrienne Rich argues that the erotic must be discovered in

“female terms: as that which is unconfined to any single part of the body or solely to the body itself, as an energy not only diffuse but...omnipresent.”

Expression in female terms means blocking out, even delusionally if necessary, the resignation, despair, self-effacement, and self-denial of sexual and gender oppression for long enough to express joy. In “Heavy Balloon,” Apple declares: “I spread like strawberries, I climb like peas and beans. I’ve been sucking it in so long that I’m bursting at the seams.”

I love the garden as a symbol for coming out: as queer, as a woman, as aware of things that systems of power want us to ignore. As a garden, coming out is less of a solution and more of a messy, entangling, enduring source of life. A garden dies and flourishes at various points, and can’t return without a heroic amount of effort. Fiona always seems to know how to do that heroic work.

Thank you so much for reading! If you enjoyed, I’d love to hear from you in the comments. And please don’t forget to like and share. Your engagement inspires me to keep writing!

Love Fiona Apple! Beautiful writing :)

She made my brother straight