A Sarah Michelle Gellar-backed reboot of Buffy the Vampire Slayer has become a real possibility.

Look. I don’t know what to say. Buffy is pretty much my entire identity. It’s been on in the background for most of my life, on repeat. I’m constantly, passively, working my way through its epic scope: its campy beginnings; its gloomy, self-serious middle years; the sixth season’s beautiful, emotional torment. It’s what I put on while I’m cooking or doing the dishes or folding the clothes. When my husband asks what I want for my birthday, I just tell him, “something Buffy related please.” I have t-shirts. I have board games. Reader: I have a tarot deck.

I don’t have a hot take on whether Buffy should return to TV. I haven’t even done much research. But these headlines are the most credible I’ve seen since reboots have begun threatening Buffy fans many years ago.

Since I can’t provide commentary on the latest news about Buffy, I’m going to tell the story about how the show came into my life as a kind of cultural Trojan horse. Too often, I’m flippant about what makes “gay culture” — iced coffee, Laura Dern, astrology. Today, instead, I want to explore in a substantive and earnest way what makes Buffy gay culture for me.

When I was a kid, I was too embarrassed to watch the shows I wanted to watch. When my dad caught me watching Sailor Moon, I’d turn it off before he saw too much and make up nonsensical explanations.

“It’s about a bunch of teenagers who come together to fight evil. They use their magic powers to kill bad guys.”

I didn’t say they were a bunch of girls in color coordinated rainbow skirts and sailor outfits. After all, Tuxedo Mask, Sailor Moon’s romantic interest, was a guy. Technically, I wasn’t lying.

What I really wanted to tell him was that I loved how the girls transformed into guardians whose magical powers complemented their interests and personalities. I loved their bright hair colors and the glitzy, dreamlike quality of the show’s 1990s Tokyo. I didn’t say those things because boys weren’t supposed to care about those things. I didn’t want him to think I was a sissy.

I concluded that if I wanted to not be alone, I’d have to train myself to like other things. Things that I could talk to other boys about. I’d have to make do with a show more like Superman or Batman. One with a big, strong hero. I would choose a new show to fixate on. A safer one.

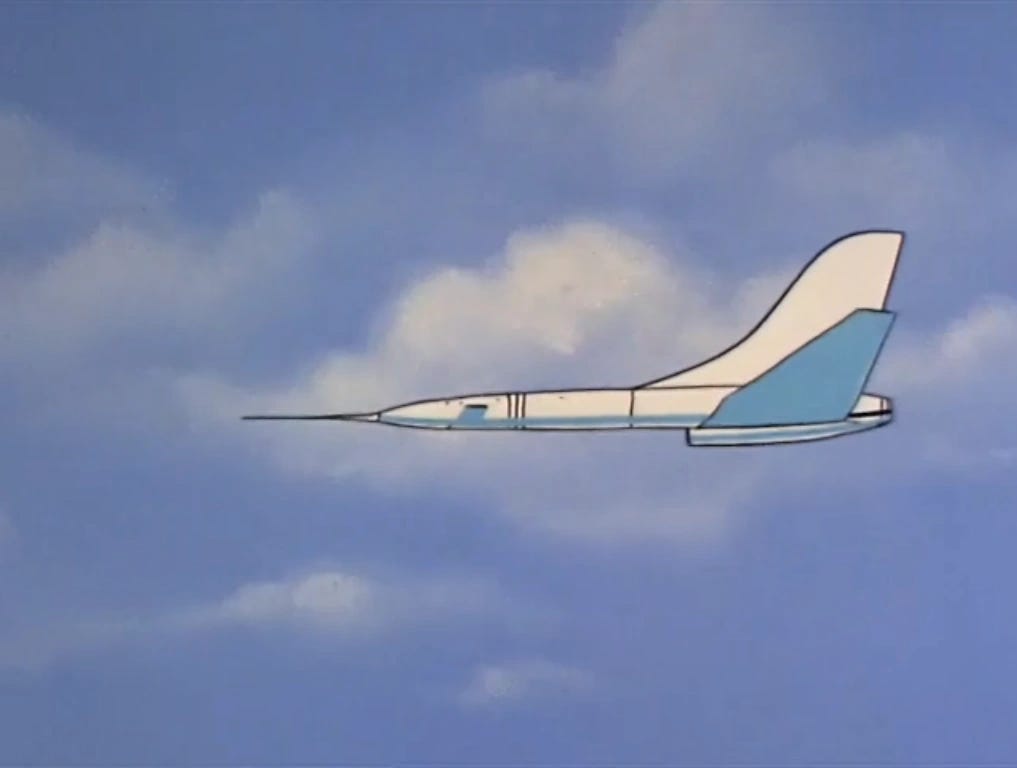

I chose Jonny Quest: a classic Hanna-Barbera cartoon that centers on Dr. Benton Quest, a widowed, renowned scientist, and his son Jonny. Together, they would zip around the world on their high-speed jet, the Dragonfly.

Jonny Quest is visually oversaturated. A solid, heavy cerulean sky chokes out the tiny white jet shooting across the screen. There’s no depth or translucence. I won’t talk around it. I’ll say it like it is. This show sucks. It’s little more than a badly written moving comic book. After the iridescent transformation sequences of Sailor Moon, the flatness of this show felt oppressive. But sometimes, it kept my dad’s attention for a few minutes longer than Sailor Moon ever could. We’d laugh together at the shoddy action sequences.

Originally airing in the 1960s, the show introduced young boys to high concept action narratives, shaping them into future fans of James Bond or Indiana Jones. Jonny is a little blonde boy whose father is a great scientist, in the mold of James Bond’s Q. Race Bannon, a “close friend” (use your imagination) of Dr. Quest, is assigned by the agency Intelligence One to live with the Quests on their private island, which is decked out with high-tech gadgets and cool vehicles of their own creation. Race’s job is not only to protect the Quests from harm, but also to educate and train Jonny in martial arts. Race’s mission is an allegory for the larger mission of the show: to teach little boys how to yearn for macho adventure stories. I was pained by how boring the show was. And yet I stoically accepted it as my mission to learn how to like it. And for years, I did.

Buffy’s pilot aired when I was in fifth grade. I learned about it in passing as my sister watched Dawson’s Creek on the WB. I’d emphatically roll my eyes at her girly tastes. But eventually, I inched my way in whenever Buffy came on and I got to see a few episodes. My sister told me the show was disgusting and stupid, which was the best news imaginable. We hated each other’s TV shows because we were a girl and a boy. But my TV show was about a girl with superpowers. How did no one notice this? How was this legal?

Soon, I had a tiny 14-inch TV in my bedroom and I’d organize my life around getting in front of it on Tuesday nights. The show is introduced as a comedy horror: comedy because a blonde girl with superpowers is funny; horror because of the monsters she fights (which sometimes are actually quite scary). It’s the perfect alibi. Boys like funny gross things.

My favorite character was Willow: a nerdy, timid redhead who eventually gains magic powers and helps her best friend, Buffy, fight evil. The male characters start in the show as prominent fixtures, but by the later seasons, they’re mostly window dressing. It was a show about women fighting evil. Full stop. Jonny Quest, eat your heart out. I was never going back.

When I was thirteen, I went on my first date with a girl. We went to see Bicentennial Man and kissed on the count of three. I’d never fully recover from the traumatic taste of her lip gloss and immediately swore it off.

In May 2000, during the Buffy’s fourth season, Willow comes out as gay. I was fourteen; it had been a year since my date, and I was starting to wonder when I’d have to bite the bullet again. But suddenly, a splinter appeared. A validation of cognitive dissonance: Willow could go from liking guys—Oz, Xander—to liking girls. Maybe it wasn’t too late for me, either?

My obsession for Buffy deepened as I reached my teens. I was a goth in high school, and without giving away too many spoilers, Willow goes through a goth phase. I was thrilled when the dark glyphs entered her veins.

A girl who liked me would often poke at me about my love for the show. She started voicing observations and questions about me: my encyclopedic knowledge of the show’s vampire and demon lore, my strong (positive) opinions about the female characters’ wardrobes, my tendency to dance effusively when the opening song came on. She started giving me looks. I started giving me looks.

Eventually, it became easier to come out than to talk around things. No, I wasn’t attracted to Sarah Michelle Gellar. Xander is more my type. And if anyone, or everyone, wouldn’t accept me, I know I had the scoobies (what Buffy’s friends called themselves) to back me up.

These days, my love for the show is not uncomplicated. Since the allegations against creator Joss Whedon came out, I have seen the show in a different light. I’ve been less convinced by the characters’ friendships knowing about the deep seeds of mistrust and self-hatred Whedon sowed in the actors behind them. I’ve felt deep appreciation for the bravery of actors like Charisma Carpenter for speaking out.

Because I’m unable to look away from reality, the show will probably not permanently remain the low, humming engine behind my life. But that is what it has been for a very long time. At first, Buffy provided cover; then, it provided clarity; finally, it gave me the push out the closet I needed. Queer theorist Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick wrote:

for many of us in childhood the ability to attach intently to a few cultural objects, objects of high or popular culture or both, objects whose meaning seemed mysterious, excessive, or oblique in relation to the codes most readily available to us, became a prime resource for survival. We needed for there to be sites where the meanings didn’t line up tidily with each other, and we learned to invest those sites with fascination and love. (Tendencies 3)

In the end, Buffy is important not only because of something special it does, but also because of its time and place. It was the cultural object present when I was getting restless, sick of pretending to like things that I didn’t. I desperately needed to attach my passions to something. While it fit in so many ways, now, I see it as only the site of fascination. Not the source. Other things move through that site freely now, and the show itself has become an arbitrary marker.

In this moment, upon news of the reboot, I have shallow feelings of dread (will the reboot be bad?) and curiosity (where will they take the show?). But the truest, deepest feeling is a detached, loving acceptance of whatever good or bad thing happens to the legacy of this show that was there when I saved myself. Buffy isn’t the hero; it’s the floatation device I grabbed onto when I was stranded. I’ve since swum to queerer shores.

love this and how it was an "alibi" since it was "horror" and allowed you to smuggle queer-coded content into your home without detection. Buffy was such a touchstone for young Gen X and older Millenials generations. something we can agree on!

Love this post, and have been writing about Buffy for a few months now, because "[someone else] kicking ass is comfort food" in these times: https://shealone.substack.com/?utm_medium=reader2